When I first picked up a camera, I thought photography was about looking harder.

Now I know it’s about learning how to see.

That distinction sounds poetic until you realize how much humility it demands. Looking is easy. Anyone with a pair of eyes and a smartphone can look. Seeing, on the other hand, is invasive. It requires patience, curiosity, and the willingness to be uncomfortable inside your own attention. Seeing means confronting the world without filters, algorithms, or the comforting illusion that beauty is convenient. It means standing still long enough to recognize that what you’re looking at is not waiting for you to understand it.

No piece of equipment can teach you that. But books can. The right ones, at least. The kind that don’t tell you what aperture to use or where to find the “good light,” but instead teach you how to think, how to observe, and how to wrestle meaning out of the mundane. The kind of books that remind you art is less about talent and more about survival. Because the truth is, if you want to become a better photographer, you have to first become a better human being, and there’s no faster way to expand your humanity than through reading.

Every photographer has their sacred texts, the ones they keep close and reread when inspiration starts to rot. They’re the books that rewire your brain, sharpen your vision, and occasionally insult your ego. They remind you that no photograph is ever finished, only abandoned; that perfection is a form of cowardice; that seeing, truly seeing, requires you to admit that most of the time you aren’t.

For me, there are five. Five books that altered not just the way I photograph, but the way I perceive. They turned the camera from a device of documentation into a compass for introspection.

Each one lives at the intersection of philosophy and practice, balancing the mechanical and the metaphysical. They bridge the gap between how things appear and what they actually mean. They’re written by photographers and thinkers who spent lifetimes trying to answer one impossible question: What does it mean to see?

And the irony, of course, is that none of them agree on the answer.

David duChemin searches for heart, Henri Cartier-Bresson for geometry, Joel Meyerowitz for grace, Daido Moriyama for chaos, and Susan Sontag for the moral cost of all of it. Together, they form a chorus. A fanatical symphony of contradictory, imperfect, endlessly human observations, and that’s precisely why they matter.

In this edition of Life Through The Lens, I want to take you through those five books: what they taught me about craft, ethics, and the elusive heart of photography. Why they continue to matter in a culture obsessed with shortcuts and style. And why I believe that if you want to make work that outlives a trend cycle, you need to study not just light and composition, but consciousness itself.

Because if photography is, at its core, the art of noticing, then reading is the act of learning how to notice yourself. Your biases, your blind spots, your longing. It’s how you build the vocabulary to describe what you’ve been trying to say all along.

In a world that scrolls faster than it breathes, these books remind us to stop, to look, and to listen. They are a gentle rebellion against the idea that art should be quick or effortless. They teach us that the camera is only as awake as the person holding it.

And that’s why, before you learn to take better photographs, you must first learn how to see through other people’s eyes.

Hello and welcome to The Creative Connection! The Creative Connection is a publication dedicated to exploring the art, craft, and business of photography. With thoughtfully curated segments, we dive into the past, present, and future of image-making. In Life Through The Lens, we spotlight influential photographers throughout history, examining their legacy and the ways their work continues to shape visual culture. Crafting A Photograph offers both technical insight and introspective guidance, helping photographers become more self-aware artists through deeper aesthetic and creative choices. Tools Of The Trade, is a series built around the gear, brands, and experiences that elevate the artist’s journey. The Creative Connection segment brings it full circle, focusing on how to market yourself as a modern photographer, build meaningful relationships both online and in person, and cut through the myths of the business side of creativity. Finally, Marks Of The Maker, is where I explore my process, philosophy, and the moments that shape my creative identity in hopes that it helps others see how their own personal work can become a mirror for who they are becoming.

This series isn’t about perfection or performance, it’s about honesty. This is more than a publication, it’s a space where artistry meets strategy.

In this segment of Life Through The Lens, we’ll be discussing 5 Books That Changed the Way I See Photography. So, without further delay, let’s jump right in!

Before we get into the craft, let’s start with the heartbeat.

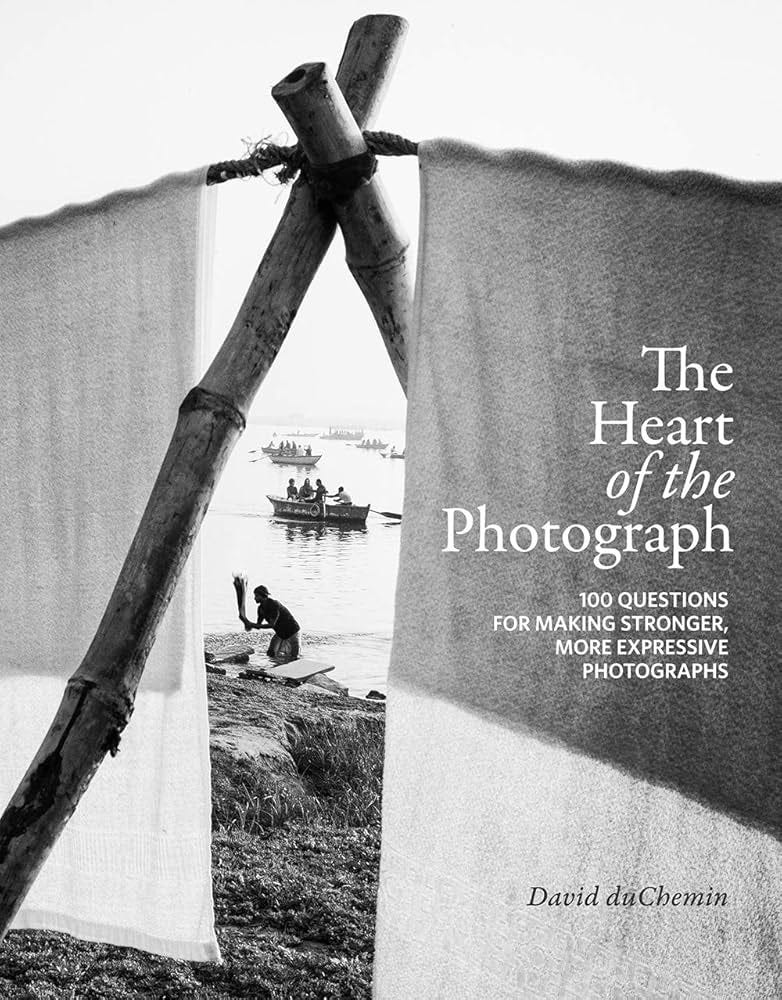

The first book that taught me how to see wasn’t about f-stops or composition grids. It was about empathy. About the emotional anatomy of an image. The Heart of the Photograph by David duChemin arrived in my hands at a time when I thought photography was something you perfected, not something you felt. It broke that illusion with precision.

DuChemin argues that photographs are not made with the camera, but with the mind and the heart. That gear doesn’t matter nearly as much as attention does. He writes, “The camera sees what you see. The question is, do you see what matters?” That line still resonates every time I read it. Because it reminds me that photography, when done right, isn’t about control. It’s about curiosity, vulnerability, and the willingness to be changed by what you notice.

I. The Heart of the Photograph by David duChemin

There are two kinds of photographers in this world: those who chase images and those who wait to feel them.

David duChemin taught me the difference, and the humility to accept which one I had been.

When I first picked up The Heart of the Photograph, I expected another well-meaning technical sermon disguised as enlightenment. The kind of book that preaches aperture as gospel and composition as salvation. I braced myself for another guide on how to get better shots, as if photography were a sport and not a philosophy disguised as one.

But duChemin didn’t hand me a manual. He handed me a mirror.

He doesn’t talk about photography as craft or commerce, but as confession. His writing reads less like instruction and more like a philosophical intervention. “The camera sees what you see,” he writes, “but the question is, do you see what matters?”

That question, so deceptively simple, was a small detonation in my brain. Because the truth is, most of us don’t. We look without seeing, shoot without feeling, collect moments without understanding them. We chase aesthetics the way tourists chase sunsets, from a safe distance, through glass, never risking the discomfort of being changed by what we witness.

Before this book, I thought the heart of photography lay in precision. In the clinical seduction of mastery. Nail the focus. Find the symmetry. Eliminate the noise. Be the invisible observer who doesn’t interfere. I thought detachment equaled professionalism. What duChemin proposed instead felt almost subversive: that imperfection is not the enemy of art but its native tongue.

He writes, “A photograph without heart is like a song without melody, technically sound but emotionally vacant.”

That one sentence dismantled years of disciplined restraint I’d built up through my own naivete. The introduction of university schooling did me no good in this regard either. I found myself at the crossroads of understanding the fundamental principles of technical photography, while simultaneously soaking up as much information on the philosophies of the craft. It wasn’t long before I became impatient and bored of the hour long lectures on lighting, composition, and shutter speeds. So, any moment I had outside of my regular class schedules, I buried my head in this book in hopes of actually learning something of value. It took only a chapter to do just that.

Because suddenly, I saw that my photographs were polite. And polite, in art, is just another word for dead.

I had been treating emotion like a liability, as though sincerity were something to be concealed behind clever framing. I wanted my work to look intelligent, elegant, balanced, digestible. I was editing the human out of my humanity. What duChemin’s book did, what it demanded, was a kind of spiritual confrontation. It asked me to stop performing for approval and start feeling again.

He reminds us that photography, at its most sacred, isn’t an act of control but an act of surrender. The camera isn’t just a tool; it is a tuning fork that vibrates to the frequency of your awareness.

“If you want to make stronger photographs,” duChemin writes, “you must first become a stronger human being.”

At first, I laughed. It sounded like something you would find printed on a tote bag in a Brooklyn camera shop. But then it stuck. Because beneath the simplicity was a challenge most photographers would rather ignore. To make stronger images, you have to live more honestly. You have to feel deeper, risk vulnerability, and embrace curiosity. You have to stop using your lens as armor and start using it as a bridge.

That is harder than learning exposure.

Let’s face it, photography attracts control freaks. People like me, who think they can make sense of chaos by framing it neatly. We chase perfection the way others chase validation, mistaking polish for purpose. We collect cameras, filters, and presets, modern-day rosaries we count instead of prayers. But all of it, duChemin argues, is meaningless without intent.

“Vision,” he says, “is the soul of the photograph.”

And vision isn’t something you buy; it’s something you bleed for.

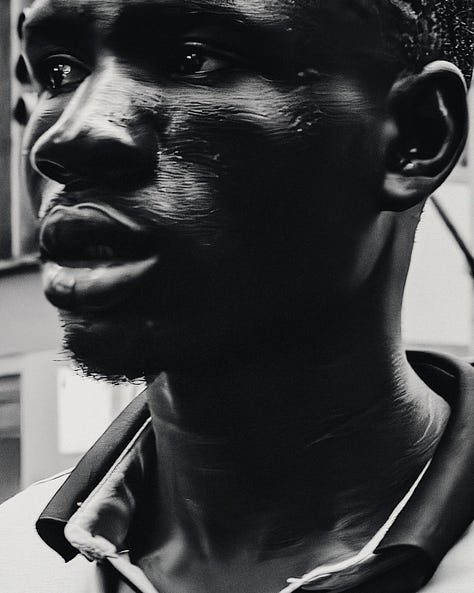

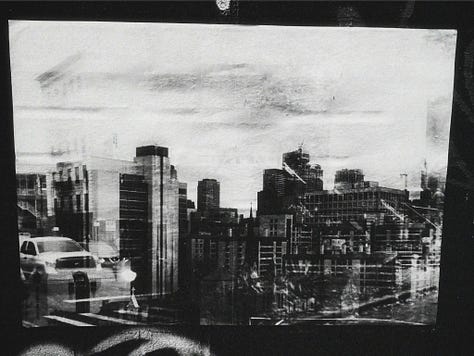

After reading The Heart of the Photograph, I began to walk differently. New York became less a backdrop and more a collaborator. I stopped looking for moments to capture and started waiting for moments to happen to me. I noticed that when you stop trying to control a scene, the world reveals itself with more grace than you ever could have arranged.

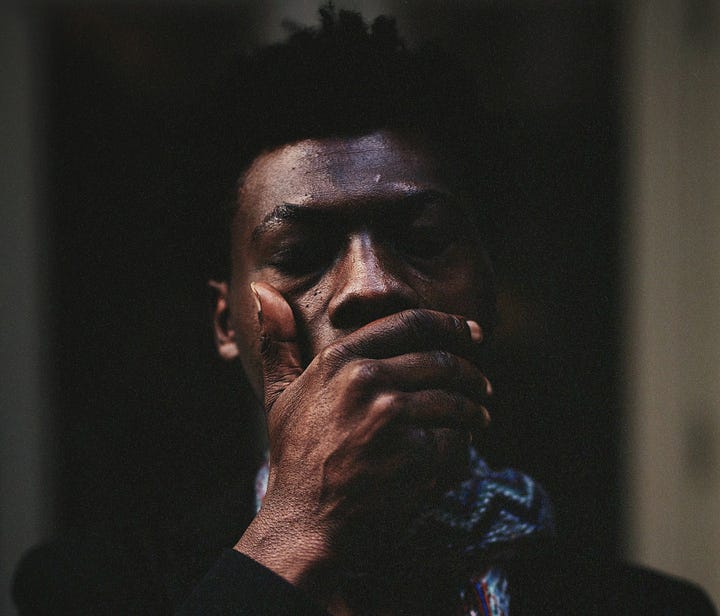

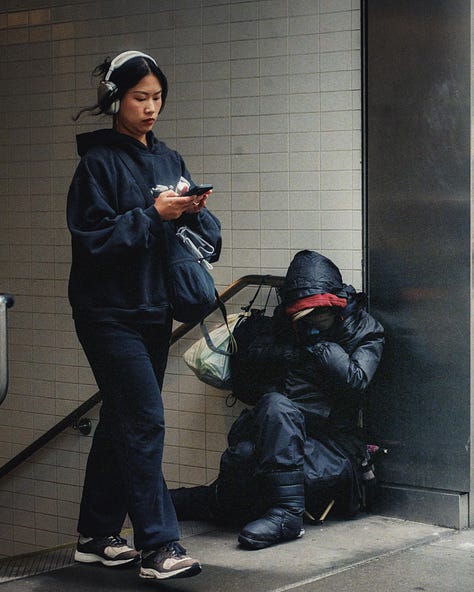

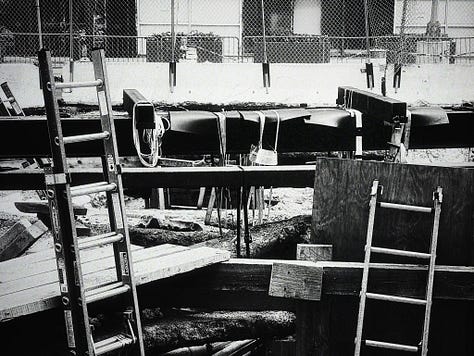

A man sleeping beneath scaffolding, the rhythm of his breath syncing with the city’s mechanical heartbeat.

A woman laughing into traffic, half-drenched in rain, half-lit by brake lights.

A street vendor counting change with the precision of a surgeon.

“Photographs,” duChemin wrote, “are not about the thing itself. They’re about the way the thing makes us feel.”

That idea changed the entire architecture of how I see. I stopped asking, Is this a good photo? and started asking, Does this mean something?

That shift, from judgment to empathy, is the difference between an image that decorates a dentists office and one that decorates a gallery.

DuChemin’s book isn’t a manual for how to make better pictures; it’s a field guide for becoming a better artist as a whole. It insists that art isn’t about mastery but about attention. That our duty as photographers isn’t to produce beauty, but to recognize it when it appears, briefly and inconveniently, in front of us.

It also reminded me that photography is less about answers than about questions. Every great image, he says, begins with curiosity. It begins with the willingness to not know. In a world obsessed with certainty, that idea feels almost radical.

If there is one thing duChemin made me understand, it is that the camera does not reward talent; it rewards honesty. The more human you allow yourself to be, the more the world will meet you halfway. The photograph is not a monument to perfection; it is an artifact of presence, proof that, for a moment, you were awake.

This book didn’t just make me a better photographer. It made me more human. Slower, softer, and less enamored with control. It taught me that the decisive moment isn’t something you take; it’s something you are invited into.

The Heart of the Photograph is a compass for those who have lost their way chasing likes, gear, or validation. It is a reminder that behind every great image is not just a skilled eye, but a heart brave enough to care, to fail, and to feel.

Because in the end, photography isn’t about what’s in front of you. It’s about what happens inside of you when you decide to look, and that is something no amount of megapixels will ever teach you.

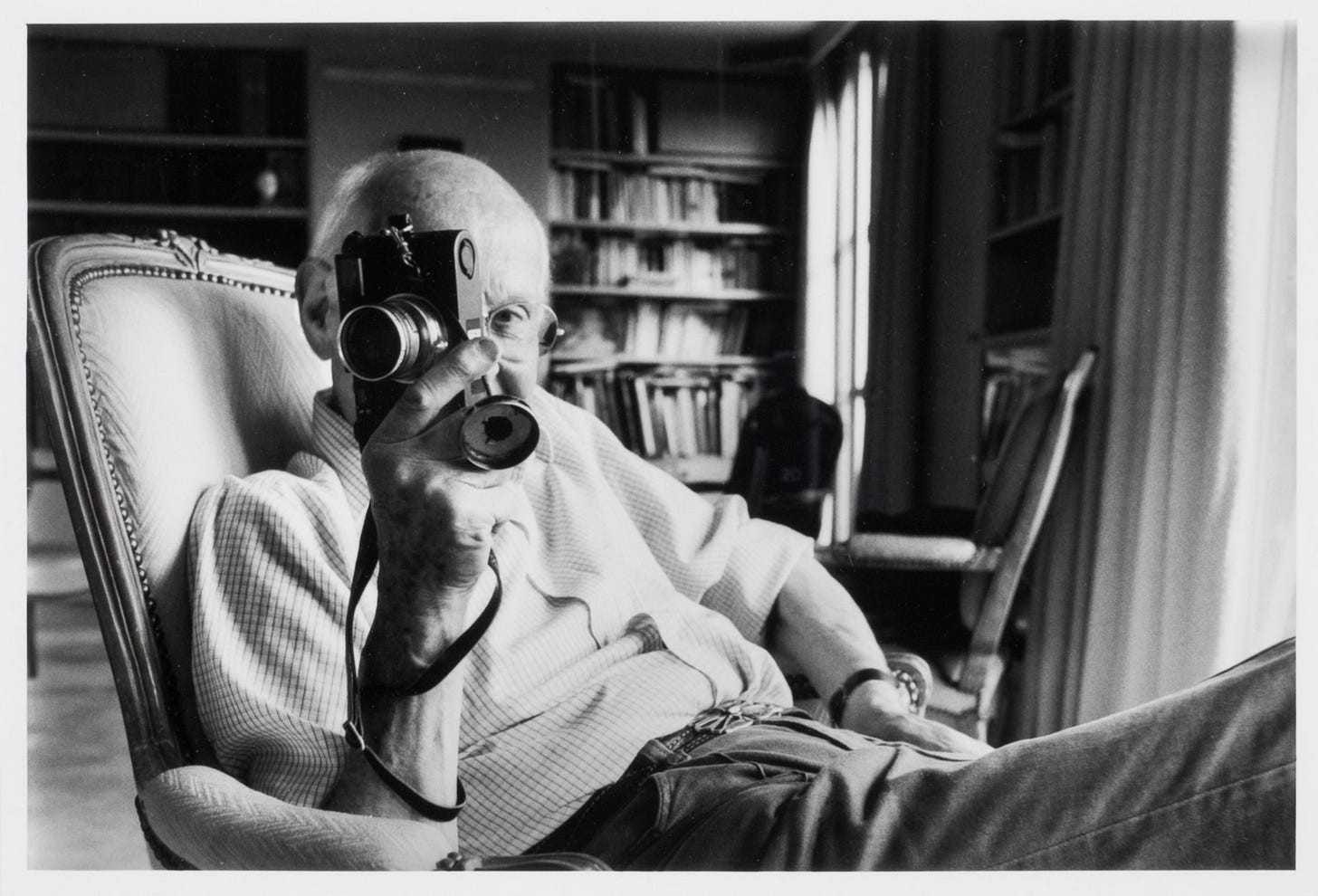

II. Conversations & Interviews by Henri Cartier-Bresson (Aperture)

Henri Cartier-Bresson did not just photograph the world. He choreographed it. His camera was less a tool of record and more a vessel of intuition. To read Conversations & Interviews is to wander through the restless mind of a man who treated photography as both meditation and combat. Every word hums with contradiction. Every sentence feels like a quiet rebellion against convention. The book reminds you that the camera, in the right hands, is both scalpel and mirror, both confession and confrontation.

Cartier-Bresson believed that the power of photography did not lie in its ability to capture the extraordinary, but in its devotion to the ordinary. “For me,” he once said, “the camera is a sketchbook, an instrument of intuition and spontaneity.” That word, intuition, is the axis of his entire philosophy. He trusted instinct more than intellect, patience more than planning. His approach to life was not that of a hunter chasing the kill, but of a fisherman waiting for the right current. The moment would arrive, if you had the humility to wait for it.

When I first read this book, I realized how much of my own practice had been guided by anxiety. The modern photographer suffers from a disease of production. We are conditioned to post, to perform, to prove. The streets of New York hum like a conveyor belt of content. Cartier-Bresson, on the other hand, was obsessed with presence. He never once spoke about “building an audience.” He spoke about “waiting.”

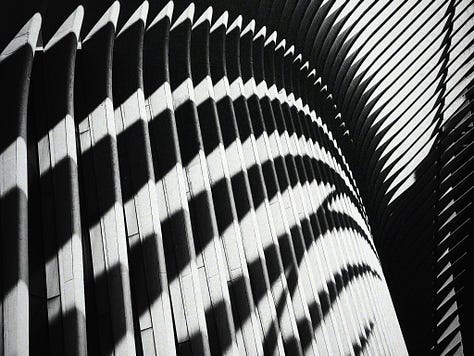

“The decisive moment,” he said, “is when everything comes together: the movement, the emotion, the geometry. It is the recognition of an order that already exists.”

That quote has lingered with me since I read it. It implies that the photograph exists before you arrive. The world is already composing itself in fleeting harmonies, and your only responsibility is to be awake enough to notice.

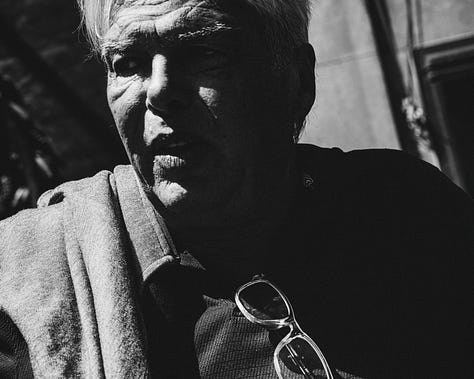

Reading this book feels like being lectured by a philosopher who has traded his robe for a Leica. Cartier-Bresson had little patience for vanity or indulgence. He mocked photographers who worshiped technique or hid behind gear. He dismissed darkroom manipulation as “cooking.” He once said, “Sharpness is a bourgeois concept,” and you can practically hear the cigarette smoke curling through the words.

What he valued instead was grace. Not the kind that appears in the image, but the kind that happens behind the lens. The grace of attention, the grace of restraint, the grace of knowing when to press the shutter and when to simply stand still. “Your first ten thousand photographs are your worst,” he joked, though beneath the humor was a painful truth. Mastery is not learned through practice. It is learned through exhaustion, through seeing so often and so deeply that your vision finally becomes quiet.

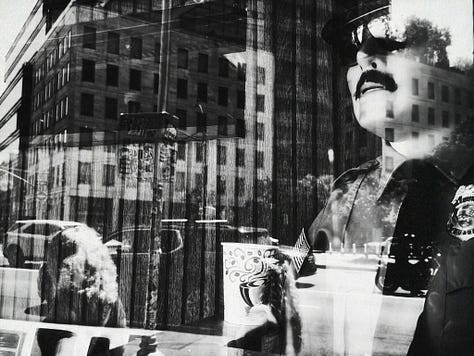

Cartier-Bresson forces you to confront a truth that most photographers prefer to avoid: we do not see. We skim. We glance. We point the camera and pray that technology will save us. We treat photography as an act of assertion when it is really an act of submission. You do not take a photograph. You receive one.

That is the lesson Conversations & Interviews insists on. It is not a book about composition or technique. It is a meditation on patience in a world addicted to speed. It teaches that restraint is not hesitation but reverence. It is a form of respect for the subject, the light, and time itself.

One story in the book has always stayed with me. Cartier-Bresson was once asked if he ever cropped his images. His answer was simple: “Never.” To him, the frame was sacred. You were given one chance. The moment either worked or it didn’t. There was no rescue in editing, no second draft. That sense of purity feels almost alien today, when photography is an act of revision as much as creation. But it carries moral weight. It demands that you be present the first time.

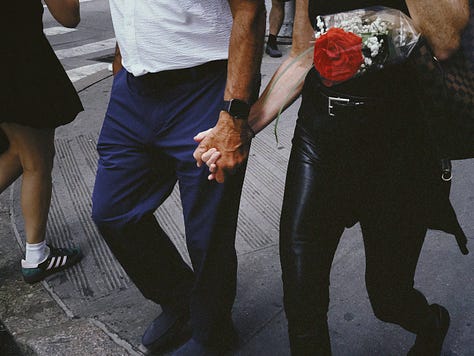

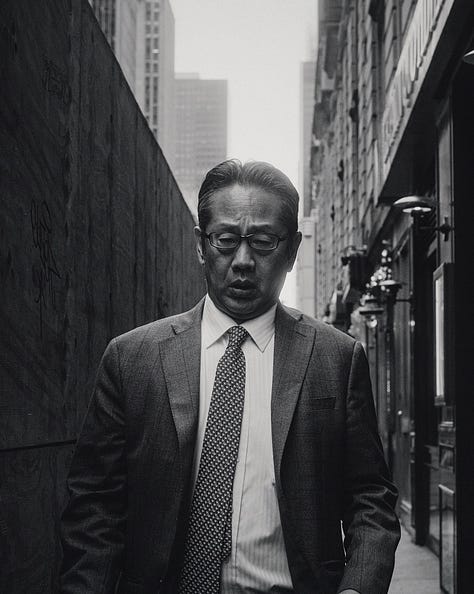

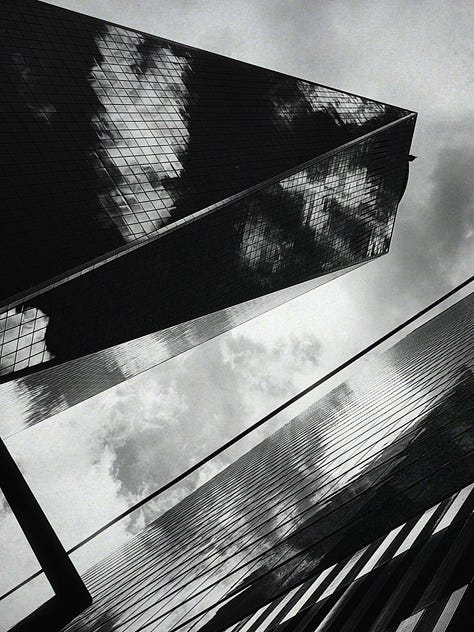

That level of attentiveness is something I try, and often fail, to live up to. New York is a study in havoc. It is a city that has declared war on stillness. Yet Cartier-Bresson’s words taught me to find rhythm in the disorder. When I am walking through the city, I think of geometry as melody. The way light cuts across the sidewalk. The way pedestrians cluster like chords. The way shadow acts as punctuation, adding silence to noise.

Cartier-Bresson turned the act of seeing into a form of prayer. He didn’t photograph to preserve. He photographed to understand. That distinction feels crucial. The photograph is not a souvenir of the past; it is an argument with the present.

In his interviews, you can feel a man who revered disarray yet refused to be devoured by it. “To take photographs,” he said, “means to recognize, simultaneously and within a fraction of a second, both the fact itself and the rigorous organization of visually perceived forms that give it meaning.” You’re not simply reacting. You’re reading. You’re reading the world in real time, decoding it, and in that act of decoding, you discover yourself.

He believed that the camera was not a tool of control but of humility. It doesn’t obey you; it corrects you. It trains you to see what you overlook. For Cartier-Bresson, photography wasn’t about expression, but alignment. He said that to photograph is “to put one’s head, one’s eye, and one’s heart on the same axis.” That image of alignment. Mind, body, and emotion. Is the closest thing photography has to scripture.

When I walk through the city, I try to remember that axis. I try to let the camera serve as a reminder, not of what to capture, but of how to be present. I stop trying to control what unfolds before me. I let the world teach me what to notice.

Conversations & Interviews did not make me a better photographer in the technical sense. It made me more aware of how easily ego seeps into the frame. It stripped away the illusion that I was ever in charge. Cartier-Bresson understood something essential: the photograph belongs to time, not to you. You borrow it for a fraction of a second before it escapes again.

What I love about this book is that it doesn’t attempt to mythologize him. It exposes his contradictions. His impatience. His arrogance. His occasional contempt for the very medium he mastered. But it is through those flaws that his humanity emerges. He wasn’t chasing perfection. He was chasing comprehension. He was trying to make sense of the world before it slipped away.

Reading Conversations & Interviews feels like rediscovering the reason I first picked up a camera. Not to freeze time, but to reconcile with it. Cartier-Bresson believed that photography existed in the fragile balance between chaos and control, instinct and intellect. And if you listen closely enough to the silence between his sentences, you realize that he was not only describing photography. He was describing the condition of being alive.

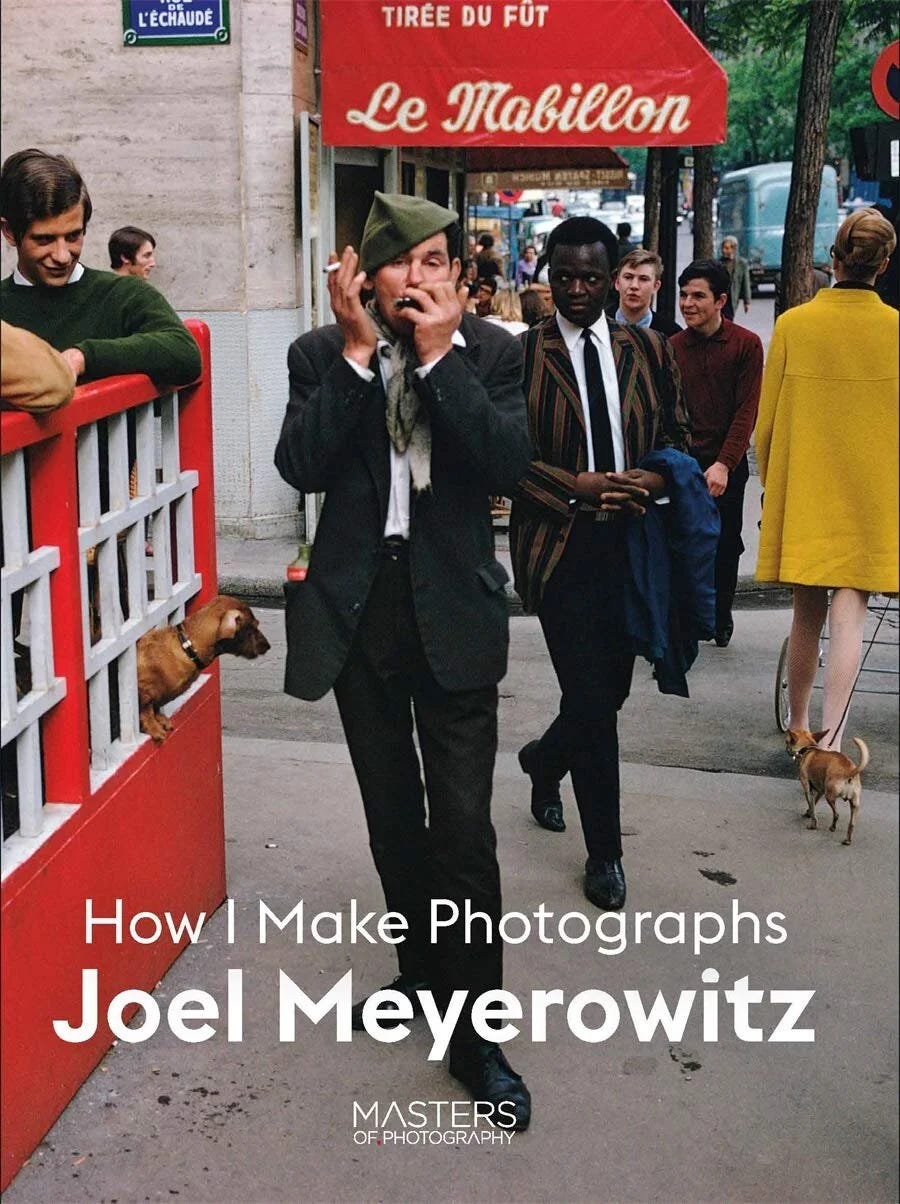

III. How I Make Photographs By Joel Meyerowitz & Masters of Photography

Joel Meyerowitz has the kind of confidence that only comes from decades of paying attention. The quiet kind. The kind earned through boredom, repetition, and failure. His mastery feels less like genius and more like endurance. He speaks about photography the way a good chef speaks about salt. With reverence. With precision. And with a patient understanding that everyone thinks they know how to use it until they ruin the dish.

His book How I Make Photographs, part of the Masters of Photography series, is not a technical guide disguised as wisdom. It is a love letter to perception. A manifesto hidden inside a conversation. Meyerowitz writes as if he is walking next to you on a crowded street, pointing at reflections in glass, murmuring about light, pausing mid-sentence to watch a stranger’s gesture unfold into poetry. His tone is both fatherly and conspiratorial. He is not trying to make you a better technician. He is trying to make you more human.

“Photography,” he writes, “is about being open to the world and allowing it to surprise you.” That sentence, at first glance, feels like something you could embroider on a tote bag. Then it begins to bother you. Because you realize how rarely we allow the world to surprise us. We scroll, we filter, we predict. We’ve built an entire culture around never being surprised. Meyerowitz, however, insists on the opposite. He suggests that the photograph begins not with the camera, but with the willingness to be humbled.

Most photographers are waiting for something extraordinary to happen. Meyerowitz waits for something honest. His philosophy is that the photograph doesn’t exist out there in the ether waiting to be captured. It begins inside you. It begins with the shape of your curiosity, with the rhythm of your breathing, with the way you choose to stand in relation to the noise of the world.

Before reading this book, I thought photography was an act of control. I believed in managing chaos, in polishing life until it looked like a portfolio. Meyerowitz taught me that photography, at its core, is participation. You cannot stand outside the moment and hope to understand it. You have to step into it. You have to let it stain you a little.

“If your pictures aren’t telling the truth of what you feel, then what are they for?” he asks. That question stripped me of every defense I had. It forced me to confront the fact that many of my photographs, however well-composed, were emotionally hollow. They were clever instead of sincere. Meyerowitz doesn’t shoot to impress; he shoots to connect. His best work feels like conversation, not performance.

Meyerowitz is a romantic trapped in the body of a realist. He understands that perfection is the taxidermy of art. His photographs breathe because he allows them to. They move, stumble, and contradict themselves. He once said that photography is “a dance between chaos and grace.” I think about that line constantly. It reframed the way I think about composition. The frame is not a cage that traps meaning. It is a stage where life improvises. The photographer is not a conductor, but a witness to the performance

.

When he describes his process, it never feels like instruction. It feels like poetry. He speaks of color the way a jazz musician speaks of rhythm, with reverence for what cannot be repeated. He treats light as a living thing. “Light reveals the moment,” he writes. “Without light, there is no event.” Light, in Meyerowitz’s world, is both revelation and reminder. It exposes what exists and makes visible what we would rather ignore.

Reading How I Make Photographs taught me something I wish someone had told me when I first picked up a camera. You need to grant yourself permission to be uncertain. Meyerowitz writes about saying yes to confusion, yes to mistakes, yes to the strange alchemy of chance. “If you’re waiting for the perfect moment,” he says, “you’ll miss the real one.” And he is painfully right. Every photograph I’ve ever hesitated to take has turned into a regret. The world never repeats itself for your convenience.

Meyerowitz’s lesson isn’t about timing. It’s about trust. You must trust that your instincts, your clumsiness, and your curiosity are enough. The camera isn’t a judge. It’s a witness. And your job is not to control it, but to speak honestly through it.

What makes Meyerowitz rare among teachers is his generosity. He has no interest in mystifying photography. He speaks with a humility that can only come from age and endurance. “What we choose to point the camera at,” he says, “is a reflection of our curiosity.” That idea transformed how I see. It turned photography from a hunt into a dialogue. I stopped trying to chase meaning. I began to listen for it.

When I walk through New York now, I see the city through his rhythm at times. Light slides across windows like sentences waiting to be written. Shadows stretch and fold into ellipses. Strangers perform accidental theatre in the periphery of my vision. I no longer look for climax. I look for coherence. I try to photograph questions instead of answers.

One of Meyerowitz’s greatest gifts is his devotion to patience. He writes about standing in one spot for hours, letting the world assemble itself into something legible. “The longer you wait,” he says, “the more the world reveals itself.” It’s a sentence that reads like meditation. It has little to do with photography and everything to do with being alive.

We live in an age where patience has been outlawed. Attention is currency, and silence is poverty. Meyerowitz refuses that economy. His book is an argument for slowness. It suggests that the act of seeing is sacred, and that rushing through it is a kind of sacrilege.

That is what makes How I Make Photographs indispensable. It dissolves the boundary between craft and character. It insists that technical precision without empathy is decoration, not art. It reminds you that a good photographer is not someone who knows how to operate a camera, but someone who knows how to pay attention. The eye and the soul are not separate instruments. They either collaborate or collapse.

Reading this book changed how I inhabit the world. It made me slower, softer, more deliberate. I began to notice the space between things. The moments that live in the margins. The gestures that reveal more than the words ever could. Meyerowitz taught me that sometimes the photograph is not the image you capture, but the awareness that you were there to see it.

He photographs as if every moment is a brief introduction. He greets the world, listens to it, and lets it pass. There is no entitlement in his work. Only curiosity. Only gratitude. That kind of humility is rare, and rarer still in a world obsessed with permanence.

For anyone serious about this craft, How I Make Photographs is not a book. It’s a recalibration. It dismantles the illusion that photography is about ownership. It teaches that the real work begins when you stop trying to make sense of the world and start letting the world make sense of you.

It’s a book about faith. Not the religious kind, but the faith that the world is still worth looking at. The faith that meaning can still be found in this mess of a reality. The faith that the act of noticing still matters.

Meyerowitz reminds us that the world does not wait for our understanding. It will never pose for us. It will never repeat itself. It only asks that we keep looking.

And that, I think, is the truest definition of art: the stubborn decision to look anyway.

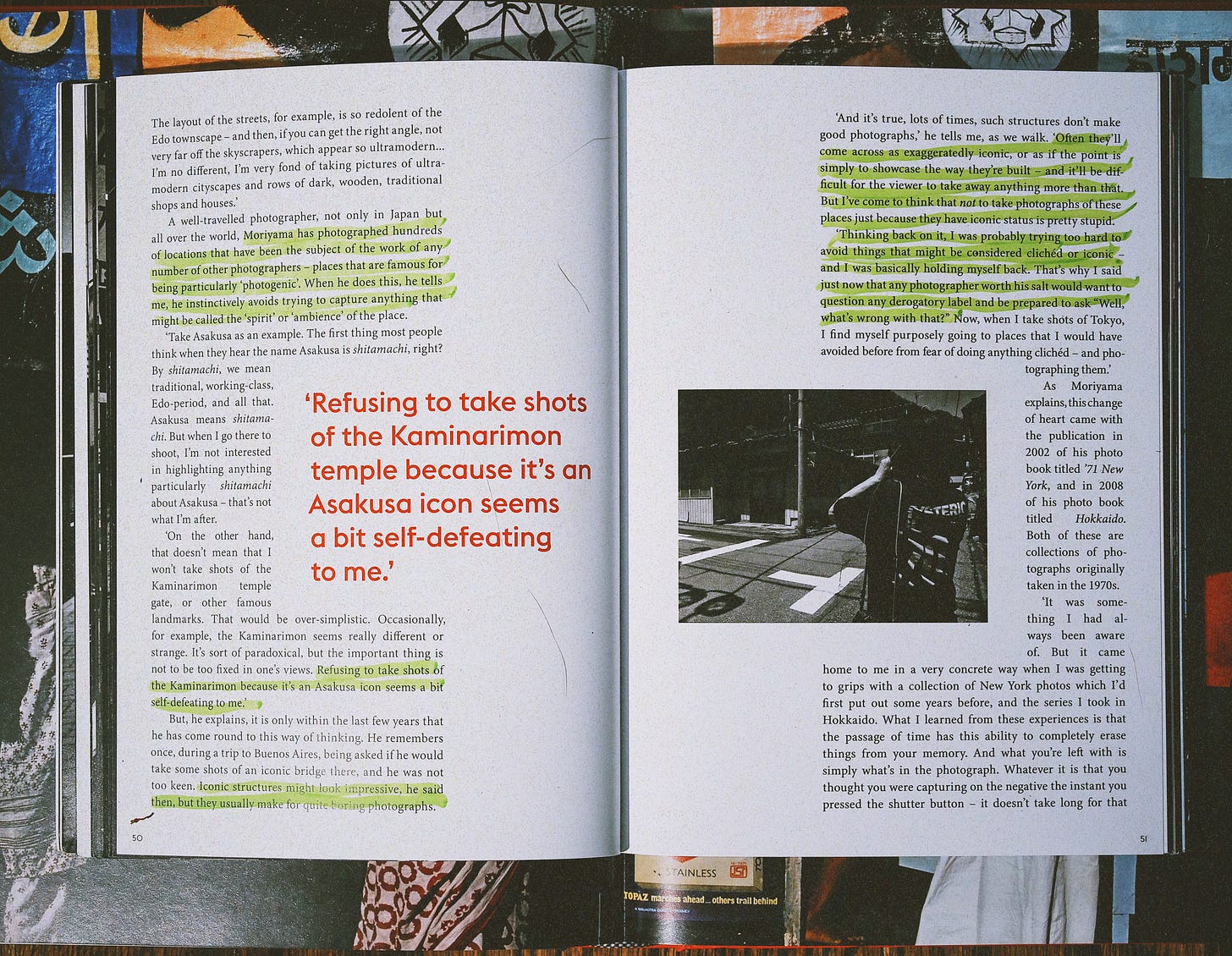

IV. How I Take Photographs: Daido Moriyama by Takeshi Nakamoto

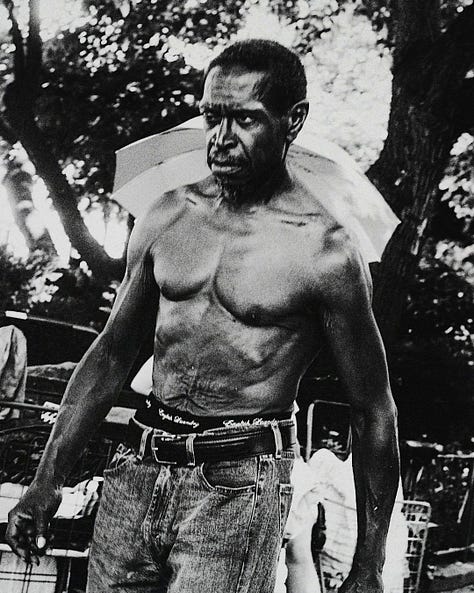

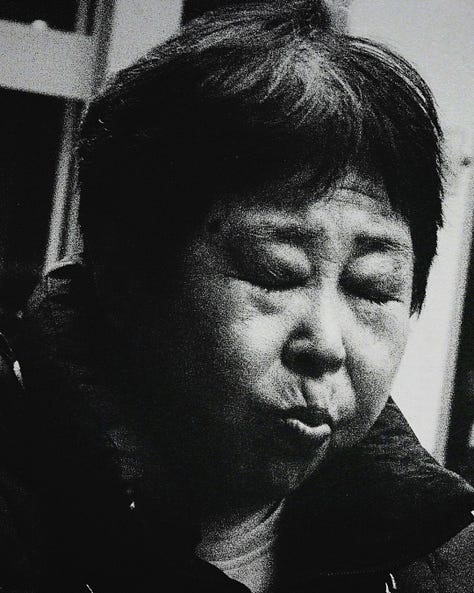

Daido Moriyama photographs like a man trying to prove the world still has a pulse. His pictures feel less like observations and more like confrontations. They don’t whisper. They bite. They stumble, snarl, and collapse into themselves, refusing the easy seduction of beauty. Moriyama doesn’t court elegance or composition. He hunts sensation. His images exist in the dirty space between comprehension and confusion. They don’t soothe. They provoke.

His book How I Take Photographs, written with Takeshi Nakamoto, is one of those rare works that dismantle everything you thought you knew about photography. It’s not a manual, not even a philosophy text. It’s a declaration of war against refinement. The book reads like a dialogue with a man who has long since abandoned the illusion that clarity equals meaning. It teaches you that the act of photographing is not about mastery, but about submission to the havoc that never stops moving.

Moriyama writes, “To me, photography is not a means by which to create beautiful art, but a unique way of encountering reality.” That line is the kind of quiet heresy that rearranges your thinking. It exposes how sanitized modern photography has become. We have turned it into an algorithmic exercise in taste. Everything is so careful, so intentional, so relentlessly edited that it forgets the dirt it was born from. Moriyama brings that dirt back. He photographs like he is digging through the wreckage of modernity to find something still breathing underneath.

Opening How I Take Photographs feels like walking through a darkroom that has caught fire. The pages vibrate with grain and with static. The prints feel overexposed, grain swelling like bacteria on film. His Tokyo is not the Tokyo of postcards or architecture magazines. (Although he does talk quite a bit about the realities of taking postcard photographs and the difficulty of making them) No, his world is a living wound. It’s concrete and cigarettes. It’s neon sweating on wet asphalt. It’s a city with insomnia, caught mid-blink. You can smell the exhaust and the loneliness. The book is less a tutorial and more an act of self-immolation.

Reading it, I realized how guilty I was of trying to civilize photography. I had been trimming its edges, smoothing its roughness, cleaning its wreckage until it resembled manners. Moriyama reminded me that control is a fantasy. The camera is not a filter; it’s a mirror dropped on the ground, shattered into reflections.

His philosophy is not just confrontational. It is brutally freeing. He is telling you, in essence, that to photograph neatly is to lie. Life is not sharp or balanced. It is smeared with confusion. His pictures are not arranged. They are caught. They show the beauty of what refuses to hold still.

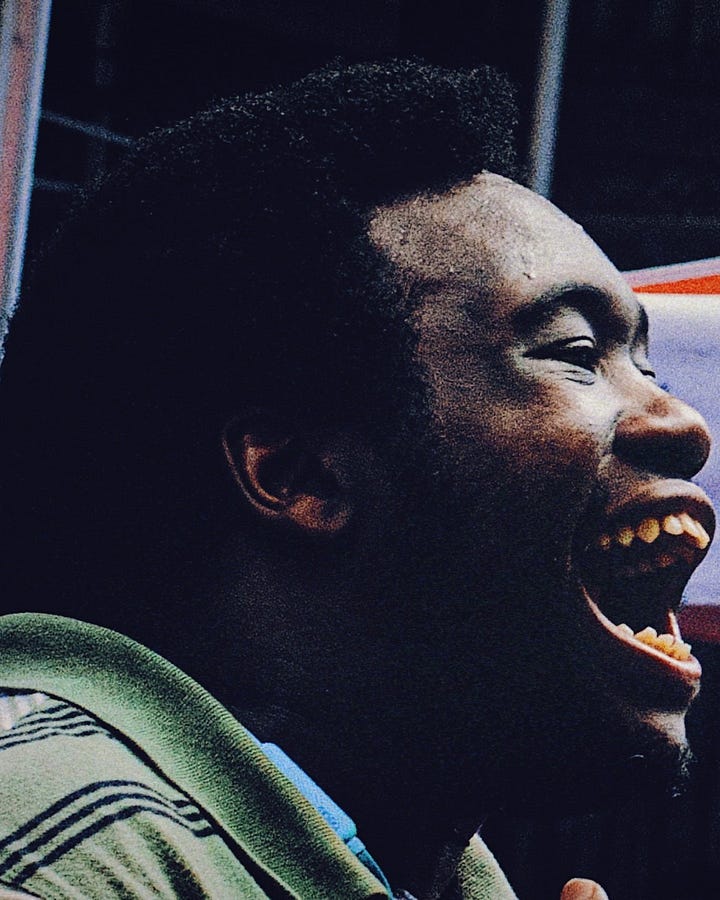

Moriyama’s images feel like the sweet melodies of a lullaby recorded in a thunderstorm. Everything overlaps. Stray dogs, plastic signs, women’s legs, neon lettering, rainwater, cigarette smoke. The city is not a subject but a mood. He photographs the underbelly of existence: the moments that decay before you can even define them. His work is proof that confusion, when honest, can be its own kind of poetry.

One of the book’s most prominent passages is where he compares photography to stray dog behavior. “You wander, sniffing around, never knowing where you’ll end up.” That metaphor has lived inside me ever since. It perfectly describes the life of anyone trying to see the world with sincerity. You wander through noise and repetition, guided only by instinct. The photograph becomes a footprint in the dirt. A trace that says, “I was here. I saw this. I survived it.”

Moriyama’s gift is that he removes all the ceremony from the act of photographing. He rejects the fetishism of equipment. He doesn’t worship Leica glass or megapixels or dynamic range. He photographs with whatever is in reach, often a small compact camera, often on the verge of breaking. “What matters most is not the camera, but the way you look,” he writes.

That line embarrassed me when I first read it. I thought of every time I had used the wrong camera as an excuse for the wrong picture. Every time I had waited for better light, better weather, better circumstances. Moriyama offers no such comfort. Photography, to him, is not about conditions. It is about compulsion. You shoot because you must. You shoot because it feels like breathing.

He writes, “When I photograph, I am not thinking. I am reacting. I am following the rhythm of the street.” That rhythm is not metaphorical. It’s physiological. His camera moves the way his heartbeat moves. His photographs feel like they were taken mid-breath, as if he might drop the camera at any second. That energy is contagious. It reminds you that the photograph is not a frozen moment. It’s the residue of motion.

Moriyama’s pictures are built on mistakes. Overexposure, blur, glare, harsh angles, grain like static. Every technical flaw becomes emotional texture. His failures are not accidental; they are essential. They reveal the gap between seeing and understanding. His imperfections are not blemishes. They are the fingerprints of experience. The photograph, to him, is not evidence of control, but evidence of surrender.

After reading the book, I walked through SoHo with his voice in my head. I stopped looking for the right light. I stopped composing. I just walked. I shot from the hip, through glass, across puddles, under streetlights. I stopped worrying about whether the shot was good. I wanted it to feel alive. I wanted it to smell like the city. And for the first time in years, it did.

Moriyama once said that a photograph should “smell of the street.” That’s one of the most accurate definitions of authenticity I’ve ever encountered. It’s the kind of line that sounds almost crude until you realize how pure it is. He’s saying that the photograph should not represent life. It should contain it.

What I love most about this book is its lack of pretension. Moriyama never calls himself an artist. He doesn’t care about legacy or galleries. He calls his photographs “evidence.” He treats the camera like a recording device for the human condition. His honesty is ruthless. Because every photograph is both truth and distortion. It shows what happened, but never what it meant.

How I Take Photographs is less a guide than a confrontation with reality. It strips away the protective layer of idealism that most photographers hide behind. It refuses the comfort of control. It insists that seeing is an act of risk. You cannot photograph honestly without losing something of yourself in the process.

Moriyama’s philosophy taught me to value imperfection as a kind of moral stance. To see blur as honesty. To see missed focus as a metaphor for time. To recognize that failure, in art as in life, is inevitable and often beautiful. His work gave me permission to stop pretending that clarity equals meaning.

Now, when I walk through New York, I carry that sense of permission with me. I move faster. I think less. I trust more. I shoot through reflections, through windows, through motion. I don’t wait for the moment. I let the moment overtake me.

If Joel Meyerowitz taught me how to listen to the world, Moriyama taught me how to feel its heartbeat. He showed me that photography should not be polite or symmetrical. It should not ask to be liked. It should challenge, disturb, and expose. It should feel like a bruise that tells you you are still alive.

That, to me, is the great revelation of How I Take Photographs. It‘s not about control or technique or the illusion of mastery. It’s about survival. About bearing witness to the raw, unfiltered mess of existence before it dissolves. It reminds you that the photograph does not belong to the photographer or the subject. It belongs to the collision between them.

And that collision, that instant of friction between seeing and feeling, is the pulse of the art itself.

Moriyama’s work, like the streets he photographs, refuses permanence. It sweats, it stumbles, it bleeds light. It is not meant to endure. It’s meant to remind you that nothing does.

In the end, the photograph is not proof that something happened. It’s proof that you were around when it happened.

And that, perhaps, is the most beautiful kind of evidence there is.

V. On Photography by Susan Sontag

Reading Susan Sontag’s On Photography is a little like arguing with a mirror that knows you better than you know yourself. You start defensive, nodding politely at her provocations, and somewhere around the third essay, you realize she’s not writing about photography at all. She’s writing about you. About your desire to see, your hunger to collect, your inability to leave the world alone.

This isn’tt a book that flatters photographers. It’s a book that exposes them. It makes you uncomfortable in the best possible way. Every time you think she’s exaggerating, you find yourself doing exactly what she warned you about two paragraphs later.

Sontag understood photography not as an art form, but as a symptom.

When I first read On Photography, I hated it. I thought it was cynical, elitist, unfair. I thought she misunderstood the generosity of photography, the way it allows us to share and empathize. But then I read it again, years later, and realized she wasn’t attacking photography. She was diagnosing the sickness that grows when seeing becomes consumption.

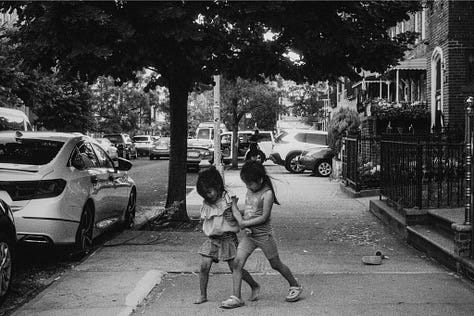

“The camera makes everyone a tourist in other people’s reality,” she wrote. That line haunted me for months. Because she was right. The modern photographer, especially the street photographer, lives in that uneasy space between witness and intruder. We look, but we also take. We empathize, but we also exploit. Sontag had the courage to name that contradiction without pretending to solve it.

She argued that every photograph is an act of aggression, a small conquest of reality. “There is something predatory in the act of taking a picture,” she said. “To photograph people is to violate them.” At first, I resisted that idea. I wanted to believe in the purity of intention, in the ethics of empathy. But the longer I photographed, the more I realized she was not accusing. She was describing. The camera does take. It turns experience into artifact, life into evidence.

That realization didn’t make me put the camera down. It made me hold it more carefully.

Sontag taught me that photography isn’t innocent. It never was. The moment you lift a camera, you are shaping memory, distorting truth, deciding what will be remembered and what will disappear. Photography is both illumination and erasure. It reveals by omission. It flatters while it steals.

What makes On Photography essential is that it refuses the comfort of moral neutrality. Sontag never suggests we stop photographing. She suggests we learn to look responsibly. To recognize that every image is a form of power. The camera does not just record; it edits the world into legibility. That act of editing has consequences.

When she writes that “photographs alter and enlarge our notion of what is worth looking at,” you begin to realize how much of your own gaze has been conditioned by other photographs. We don’t see the world directly anymore. We see it through its reproductions. Every corner of New York, every face, every tragedy has already been photographed a thousand times. The task now is not to document reality, but to recover sincerity from its exhaustion.

That was Sontag’s gift: she made you suspicious of your own seeing. She forced you to ask uncomfortable questions. Why this subject and not another? Why now? Why me? What am I trying to prove by looking?

Her critique is as relevant today as it was in 1977, maybe even more so. In a world where billions of photographs are made daily, her essays read like prophecy. She predicted the age of visual fatigue, the endless scroll of images divorced from context. “A photograph,” she wrote, “is both a pseudo-presence and a token of absence.” It is proof that something was there and, simultaneously, that it is gone. Every image carries within it the quiet grief of what can never return.

That paradox is the soul of photography. And Sontag, perhaps more than anyone else, understood its tragedy.

When I first began photographing seriously, I believed I was capturing reality. Sontag made me realize I was constructing it. Every frame was an argument, every composition a claim. The camera was not neutral; it was interpretive. That shift changed everything about how I work. I stopped pretending to be objective. I started acknowledging that my gaze carries bias, history, and longing.

Sontag also made me wary of aestheticizing suffering. She warned against the danger of turning pain into spectacle. “The camera,” she wrote, “makes reality atomic, manageable, and opaque.” That line cut deep. Because I had done it, as we all have. I had turned the suffering of others into beautiful composition. I had photographed a man sleeping on a bench and thought about lighting before I thought about his name.

Her book made me more patient. More hesitant. More human. It taught me that not every moment is mine to take, that sometimes the most ethical act of seeing is to simply look without the mediation of a lens.

What separates Sontag from her critics is that she loved photography enough to interrogate it. She was not a puritan or a pessimist. She was an examiner of the human impulse to look. She understood that photography is both proof of our empathy and evidence of our distance. It connects and isolates in the same breath.

Reading On Photography now feels like reading scripture for an age of excess. It’s not comfortable reading. It shouldn’t be. It’s a mirror that refuses to flatter. It does not offer resolution. It offers accountability.

Sontag believed that photographs alter not just what we see, but how we see. They teach us desire, empathy, and indifference all at once. “To photograph,” she wrote, “is to appropriate the thing photographed.” And yet, she also admitted that photographs expand our sense of the world. They make it larger, more complex, more unbearable, and more beautiful. That tension is the truth of the medium.

What I took from On Photography is not guilt, but awareness. Awareness that photography isn’t just a visual act, but a moral one. That the image has consequences. That to photograph is to decide what the world remembers.

And maybe that is what makes her writing so essential for anyone serious about this craft. It reminds us that photography, for all its poetry and beauty, is also a form of responsibility. To see is to care. To care is to act.

Sontag understood that the camera’s power is both creative and corrupting. It gives us the illusion of understanding the world while often distancing us from it. The challenge is to close that distance, to make the act of seeing sacred again.

I don’t always agree with her. But that’s the point. Her writing isn’t meant to be agreed with. It’s meant to wake you up. It’s meant to make you aware that every time you lift a camera, you are participating in the history of how humanity sees itself.

On Photography is not a celebration of the medium. It is its reckoning. And yet, in that reckoning lies its beauty. Because Sontag, for all her skepticism, understood that we photograph for the same reason we write, paint, and dream. To remember. To bear witness. To insist, against time and indifference, that we were here and we saw.

In the end, Sontag doesn’t teach you how to take photographs. She teaches you how to live with them. How to carry their weight. How to see through their illusions without losing your faith in the act of looking itself.

That’s her gift. She leaves you wary, but awake.

Because to see consciously, in this world, is already a kind of resistance.

Closing Note: Keep Reading, Keep Looking

If photography teaches us how to see, then books teach us why. The longer I work, the more I realize the two are inseparable. Reading shapes the eye as much as experience shapes the heart. Every sentence I underline becomes a kind of photograph. A still frame of someone else’s attention that sharpens my own.

The five books I shared here aren’t manuals. They’re mirrors. Each one asks you to look at the world differently, but more importantly, to look at yourself differently. They remind you that vision is not just what enters the camera, but what you choose to let stay inside you.

So, if this piece finds you in a creative rut, pick up a book instead of your camera. Let someone else’s mind recalibrate your sight. Study how Cartier-Bresson waits, how Meyerowitz listens, how Moriyama wanders, how Sontag interrogates, how duChemin feels. Read until you start to notice differently.

And when you do, take your camera and step outside. The world will look new again.

I’d love to know what books have changed the way you see. What words have rearranged your vision? Leave a comment, share your own list, or tell me the one line from a book that has followed you into the streets.

Because photography may teach us to see the world, but reading reminds us why it’s worth seeing at all.

Thank you so much for reading this edition of Life Through The Lens. It means the world to have you here on this journey with me. If you enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing so you never miss a new publication. There’s so much more to come, and I’d love to have you along for the ride.

As a photographer, storytelling through imagery is my passion. If you’re curious about my work behind the lens, feel free to check out my portfolio. I also share visual companions to articles like this one over on my YouTube channel, perfect for those who enjoy a more immersive, visual experience.

I believe education and inspiration should always be free. But if you’d like to support me and The Creative Connection, consider buying me a coffee using the link below. It helps fuel late nights, big ideas, and future editions of this series.

Thanks again for being here—until next time.

[Buy Me a Coffee ☕️ – Link below]

What a terrific list. I’ve been friends with David duChemin for about 15 years and he is one of my favorite humans ever. We’ve recorded multiple conversations and they always go somewhere unexpected and inspiring. I would add Road to Seeing by Dan Winters (who I’ve also recorded with) to that list. Unfortunately, it’s now out of print and hugely expensive on the secondary market.

Hello algorithm, thanks for serving up this gold